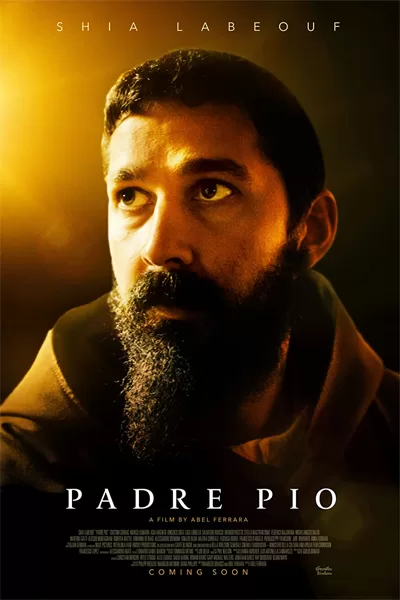

- Starring

- Shia LaBeouf

- Director

- Abel Ferrara

- Rating

- R

- Genre

- Biography, Drama

- Where to watch

- Vudu (rent or buy), Amazon (rent or buy)

Overall Score

Rating Overview

Rating Summary

Some of the richest and most fascinating stories can be found in the lives of the Saints. A cursory review of their impeccable character, unreal journeys, and dramatic engagements with the world is enough to wrestle a soul from its sluggish and sedentary stupor to begin pursuing haughtier goals. The need for such stories to be told with vigor, finesse, and artistry cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, Pio starring Shia LaBeouf is not this kind of storytelling.

Padre Pio is a snapshot of the early life of the real-life Catholic saint and mystic. The film is set in the Italian town of San Giovanni Rotondo around the end of the first world war, circa 1918. Political pressures have been mounting as, in an effort to overthrow the town’s bourgeoise, a young socialist party has begun to rally the town’s workers in an effort to gain leadership through the newly minted democratic process. Meanwhile, Padre Pio has just arrived at the town’s monastery to begin his priestly duties.

As early as the opening shot, the film’s low quality is immediately clear. We see Pio riding a donkey through a mountain pass to the monastery to join his religious brethren, and the cinematography feels more like a home video, giving no sense of wonder, suspense, beauty, or intrigue. Instead, we are treated to amateurishly prolonged long shots and awkward close-ups that do little more than confuse the eye.

Without warning, the scene quickly and jarringly cuts to the town’s streets, where soldiers return home from battle to greet their families, with every moment shot in an overly gritty manner, projecting nothing but misery. While there is nothing wrong with a gritty style, in this instance, it is the only style throughout the film and serves only to weigh every moment down in despair and hopelessness. A movie about a saint should have some hope.

From one shot to the next, there is nearly zero cohesiveness, and the cinematography alternates between jarring, sloppy, and uninspired. This is evidenced by the inexplicable and disruptive directorial decision to overuse and abuse the shaky cam. Director Abel Ferrara’s reliance on the technique is chaotic to the point of causing motion sickness. In what is arguably the quintessential example of the filmmaker’s ineptitude, there is a shot of the townspeople leaving mass, in which the camera is clearly bumped into by one of the actors.

While the acting is not Disney Channel bad in the film, it’s also not in danger of winning any accolades but is instead consistently wooden. Shia does a fine job, giving a mostly authentic performance, but the audience never quite feels like they’re watching Padre Pio. Instead, it’s as though Shia is playing out his own conversion on camera. At times this can be captivating but, again, does nothing to further the narrative.

In an already troubled production, there were a few especially weak performances, that of the young revolutionary Luigi (portrayed by Vincenzo Cera) and the town’s mayor (portrayed by Salvatore Ruocco). Luigi is introduced as the socialist visionary there to inspire the townspeople to join the movement aroused by what is supposed to be a jolting speech/Q&A in the streets. Throughout this sequence, the actor appears uncomfortable and uncertain of himself during a time when the character is meant to be exuding confidence.

The actor playing the mayor seems to forget his lines at times, appearing like bad improv. There is a scene where he is gathered in his opulent home with other members of the ruling class to nefariously plot a way to ensure the elections go in their favor. As he is speaking with his conspirators, he not only stumbles through the dialogue but makes the audience cringe while he does it due to his obvious discomfort. This scene is where he is meant to be the top dog, a confident and menacing character.

Not helping any of the performers, much of the dialogue is robotic and forced, with nearly every line feeling as though it needed to justify its own existence due to the film’s complete lack of logical continuity or natural flow. In the scene just described above, the mayor, in a stream-of-consciousness, states, “I was talking to Don Anselmo. We were making final plans for the election…I’m sure I will win. I mean, I have no doubt about it, but if the other side, they create a riot or if they, like, manipulate the actual voting that, that, could be a problem.” The military leader, whom the mayor is talking to, then states, “That is why I am here” At that point, another person in the room monologues about why this matters saying, “I’ve been away at the front for so long, you know? I fought for two years, and then I come back here, you know, and I have to worry about all this…” going on to talk about the election some more. The interaction and the dialogue are on par with a high school play.

In general, the story is incoherent and vague, taking nearly the whole of the movie for the audience to gain some understanding of what the filmmakers are trying to convey. Only at the end (i.e., the final 10-15 minutes) of the movie is it explained that Pio has been suffering in concert with the sins/sufferings of the townspeople. This, however, is not some swelling revelation that has been percolating throughout the film through clever or creative direction, though it most certainly should have been. Rather, Pio simply utters a hamfisted line that clues the audience in that this is what has been happening throughout the entire film. Even then, the nature of his connection to the town is unclear.

If all of this were not enough, what was heretofore the B story (the socialist uprising) suddenly and without rhyme or reason becomes the A story, yet with no real reason given for the audience to care about any of it and no understandable connection drawn to Padre Pio. Incomprehensibly, the audience finds itself following the story of a random villager whose husband did not return from the war. It’s clearly intended that the audience be tied to her as their emotional barometer for the film. However, she is miserable with no redeeming qualities and gives the audience no real reason to care about her perspective. In the end, her arc is that she develops a love for socialism so deep and intractable that she is martyred for it.

One might assume that Pio, being the titular character as well as being responsible for the spiritual well-being of the locals, would have significant interactions with the townspeople. One would be wrong. There are a total of two encounters in the film’s entirety; once, he hears a confession, and once, he prays at a deceased villager’s wake. Considering how rich the life of the real Padre Pio was, in this travesty of a film, it is made to feel thin and utterly unrealized, instead spending far too much of its time bouncing back and forth between the socialist uprising and Pio in the monastery/church with no sense or purpose.

In yet another in a never-ending string of mystifying choices, there is one of the film’s multiple scenes in which Pio is battling the devil, and this time while in the confessional, Pio profanes, using the “F-word” whilst rebuking the devil. Again, this felt more like we were watching Shia LaBeouf battle his own demons rather than Padre Pio. It was heartfelt and sincere but disconnected from the reality of this literal Saint. Incomprehensibly, Padre Pio’s character was barely established during the movie. Rather his development relied on a mere handful of expositional discussions between another friar and himself.

As problematic as the film is, in one of two confessional scenes, Pio offers spiritual counsel that includes a rich spiritual metaphor that is truly edifying. This and his battles with the devil are compelling. However, any good in the film, which is sparse, is completely decimated by two horrifyingly graphic and gratuitous scenes. In one, the devil takes the form of a nude woman and behaves in a pornographic/sacrilegious manner to tempt Padre Pio. Assuming this was an accurate accounting, it could have easily been handled more creatively and modestly while conveying the same effect. In the other, Shia is nude while again battling the devil. In it, he reveals his backside, which feels unsettling without artistic value. The scene itself was disturbing enough. There was no need to see Shia in LaBuff.

In large part, thanks to uneven performances, amateurish cinematography, inexplicable directorial decisions, and glacial pacing, Padre Pio is a scattered, incoherent, and boring mess. Like really, really, really boring. So boring that every 20 minutes feels like an hour and a half. It’s not only a disappointment but an incredible missed opportunity. If you want to watch a Christian film that is uplifting and well done, take a look at Jesus Revolution.

WOKE ELEMENTS

- The socialists are depicted as sympathetic characters who quote scripture and “church teachings” to justify their socialist ideology. The Church does not support nor has ever supported socialism/communism.

- The bourgeoisie class is heartless and ruthless one-dimensional villains. This is not to say that these kinds of people don’t exist or that Italy did not have problems, or that it was not in need of reform, but this comes across as another attempt to lionize socialism as the “Christian way” and demonize “capitalism” even though these guys are not capitalists.

Michael Carrick

Michael Carrick is a cinephile and professional clinician with a master’s degree in psychology, so he is trained to spot pathology in all its iterations. Michael has sought to help people heal and uncover the deeper themes, meanings, and purposes in their stories to aid them in living a better life. He now aims to help heal the film industry by shrinking it as well, and hopefully squeeze out the pathology. He relies upon his passion for film and psychological foundation, which includes strong philosophical and theological fundamentals to analyze film, highlight the artistic value and offer a diagnosis.